Dublin Bay’s Premier Underwater Reef-Former Kate McGonagle

Intro to Kelp

This month we are diving into a group that I have had a particular fascination with – kelp. Kelp are the foundations of temperate reefs in our shallower waters, and they are home to countless different species. A patch of this brown seaweed can support whole communities; lobsters, crabs, fish, shark eggs wrapped around their stipes, or stems, and even supporting other seaweeds growing on the surface of them. We have a huge variety of seaweed species here in Ireland, and kelps are of special importance for their own unique reasons.

So, what are they? Although at first glance you might mistake kelps for plants, they are actually algae. Algae can be divided simply into three categories – brown, green, and red. Kelps are a group of brown algae, and at about 450 million years old, brown algae are the newest group. Algae are a hugely broad grouping of lots of different species, from tiny photosynthesising bacteria to the green sheet-like algae covering rocky shorelines. They can be single-celled, in filaments, or complicated multicellular organisms, the diversity never ends – you can even find them teaming up with fungi on trees, or colouring the sides of buildings. They are arguably one of the most important groups on the planet, with phytoplankton supporting the oceans’ food chains, to kelp forming the coastal habitats.

Kelp have quite a complicated life cycle. They release spores which develop as either male or female gametophytes once they are attached to something. These are microscopic, and the male will then release sperm into the water, which finds the females eggs through chemical signals. After fertilisation, the female gametophyte develops into the kelp plant we commonly see while diving.

Different types of Kelp in Dublin Bay

We are lucky enough to have a high diversity of kelp species around our coasts. It is impossible to cover all of the amazing uniqueness of each of our species in such limited time, because each comes with their own interactions with other seaweeds, their own community structures, and their own importance to local areas. Broadly, some of our key kelp families are the Laminaria, Alaria, and Saccorhiza species.

The kelps we often see around Dublin Bay with round stipes, and large, flat blades are usually one of two species of Laminaria: Laminaria digitata, and Laminaria hyperborea. These two kelps are found all around our coastlines and are probably the most easily recognisable of our kelps. Sacchoriza looks similar, but its stipe is wide and flat, rather than round. Another Laminaria species, Laminaria saccharina, or sugar kelp, and Alaria esculenta, can also look similar to each other, with a large stipe through the middle of their long “frilly” blades - Alaria appears narrower and less frilled at the edges.

The big difference between all of these species is where they can be found. You can tell a lot about what species you are looking at based on depth and the conditions in the water. Laminaria digitata is found in water that won’t be exposed to the air, and can tolerate pretty strong waves and currents, while L.hyperborea is mostly in much shallower areas or very clear water (Laminaria Digitata, seaweed.ie). The others can all be found in these same zones, as well as slightly higher, where they can be exposed at very low tides. Laminaria saccharina can’t cope with as much wave action and this limits its distribution to areas that are a bit calmer. Alaria can withstand much stronger waves, but it cannot outcompete Laminaria digitata in these lower zones unless the wave action is really strong, so it is limited to shallower, and slightly deeper rougher areas (Werner and Kraan, 2004). These species are in constant competition with each other, with grazers, light availability, currents, and tides all having a role to play in who will win out over the other. Werner and Kraan, 2004 from the Marine Institute have published a really interesting review which shows these species in a table and explains it further: https://oar.marine.ie/handle/10793/261

Alaria esculenta

Laminaria digitata

Laminaria hyperborea.

Laminaria saccharina

Kelp Importance

Kelp are the foundation of temperate reef systems. They are a vital part of the community, associated with high biodiversity, providing food and shelter, and protecting their communities from the oceans’ waves.

Kelps are such important nursery grounds for huge range of fish species like saithe (Hoeisaeter & Fossaa, 1993). Nursery grounds offer food, shelter from the elements, and protection from predators. Next time you are out on a dive and come across some, take a look at the fronds, or blades, because you will probably see small patches of red or green algae growing there, and oftentimes our coastal shark species like the small-spotted catshark will wrap their egg cases around the base of a piece of kelp to blend in and allow it to grow into a baby shark.

Of course, we can’t talk about kelp without talking about photosynthesis. Algae know photosynthesis better than any other species on the planet. The first photosynthetic organism was a cyanobacteria, a type of algae which is still around today. In fact, plants inherited this ability from cyanobacteria, as plants gained the ability to photosynthesise by engulfing cyanobacteria into their own cells. By photosynthesising, kelps take carbon from the atmosphere and store it, produce oxygen for their own communities, and for the surrounding waters. We still do not have a full understanding of just how important kelps are in carbon storage, but we know that they have a valuable role to play. Ocean warming means kelp distributions are going to change, but with barriers to movement like suitable seafloor for them to attach to, and the fact that they cannot simply swim like a fish can, it is more important than ever to protect kelp for how valuable they are to the earth, their ecosystems, and to us.

Invasion

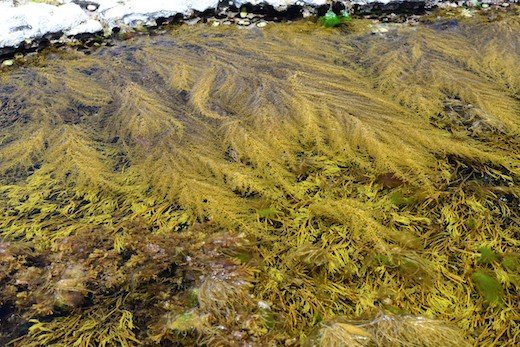

Despite how abundant kelp is when you take a look around common dive sites like Dalkey Island, the threats are never far away. Across our island, our coastal seaweeds are reckoning with a new threat. Since its discovery in Strangford Lough in 1995 (Boaden, 1995), Wireweed has spread throughout our island. Wireweed, known scientifically as Sargassum muticum, is a native Japanese brown seaweed that has been appearing in more and more areas as an invasive. It was documented in the UK before it appeared here and has been seen spreading since then. We think that it is spread through boats and shellfish transport, and that this is part of the reason it has been able to colonise so much of the country in a relatively short time. One study found that Sargassum colonises about 54km of the Irish Coastline each year (Kraan, 2008).

Sargassum from below and above the water

Photo: left:https://www.nonnativespecies.org/non-native-species/nnss-image-gallery/view/902; right: https://seaweed.ie/sargassum/index.html

Sargassum wreaks ecological havoc on the areas it invades; it outpaces our local kelp species in growth and reaches up taller in the water column, blocking light from the kelp below. By outcompeting native species, this can reduce kelp abundance, and affect grazers which consume them, as well as other reliant species.

What makes Sargassum so difficult to control is its reproduction. For some invasive seaweeds, local efforts physically removing them have seen success in controlling the spread. Sargassum, however, can reproduce through fragmentation, as well as sexual reproduction. This means that when sargassum is broken, the fragments of the original organism each can grow into a new one, and it is quite brittle. Attempts to physically remove Sargassum can actually cause it to spread more quickly, because it only takes two tiny pieces to break off of each individual for the efforts to have actually doubled the problem. If you encounter Sargassum on a dive, make sure not to touch it, and look from a distance to avoid accelerating the problem.

Sargassum from above the water

Sargassum from below

While Kelps may look unassuming to a diver if you are on the lookout for fish, try taking a closer look at these communities, because you never know what you might find, just make sure to not disturb them.

Bibliography

Boaden, P. J. S. (1995). The Adventive Seaweed Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt in Strangford Lough, Northern Ireland. The Irish Naturalists’ Journal, 25(3), 111–113

Hoeisaeter T, Fossaa JH (1993) The kelp forest and its resident fish fauna. Report No. 8, Institutt for Fiskeri og Marinbiologi, University of Bergen, Bergen

Photographs: https://seaweed.ie/

Kraan, S. (2008). Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt in Ireland: An invasive species on the move. Journal of Applied Phycology, 20(5), 825–832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-007-9208-1

Werner, A., & Kraan, S. (2004). Review of the Potential Mechanisation of Kelp Harvesting in Ireland. https://oar.marine.ie/handle/10793/261